Bookstore Creep : Hikuri from Mother Foucault

Through wide glass panes the creaking of enormous city buses dropping off their passengers and the cars whooshing by are muted. Mother Foucault is located close to the bridges that mark the end of inner Southeast Portland. The shop itself is a wooden, multi-tiered strangely-shaped space overseen by Craig, who has been contentedly holding down the past. Vacuuming when I walked in, he greeted me unconcernedly and continued with his chore, then out for a fraction of a cigarette, and lastly to settle at his desk. In the handful of minutes before I could strike up a conversation I explored the many corners of the shop, noting that there were quite a few shelves devoted to titles in different languages. I also noted that any bookshop that has remained open and cheerful despite inflation and the internet should be considered a natural wonder of the world.

I had been humbled by my last bookshop investigation. I had optimistically ventured downtown to visit Daedalus books, a spot that I knew to be particularly academic and worldly. I asked the owner my research question: “What modern-day writers do you know of that are writing about or are a participant in the counterculture or the underground, in the general vicinity of North America?”

My investigation was redirected almost as soon as I opened my mouth. A long pause as the owner scratched his ear and typed nervously into the database. Nothing is coming up under the search-term ‘counterculture’. He politely pointed me here, which I consider a humble and martyr-like action, even if it was driven by anxiety. I noted that I am essentially playing a game with strangers, and that some may be shocked by that. Perhaps especially the bookish types, who may prefer their prompts written instead of verbal.

Nevertheless, the investigation must go on. The results were more favorable this time around.

Craig has an unconcerned, slow way of speaking, no interest or connection to the internet, and an old-school phone complete with the curly cord. An impressive feat for a bookstore in the center of a hub of activity; surrounded by tacos, music venues, strip clubs, and expensive ramen. One night I was drawn to execute a reconnaisance drive past the establishment, and I could have sworn that I glimpsed a circle of old men with long beards gathered there while swarms of people funneled into nearby bars to get sloshed. Whether or not the mirage was real, it summed up the contrast between this establishment and its surroundings.

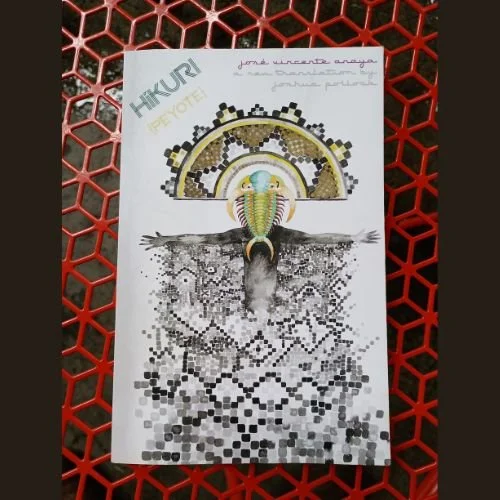

Slowly, we made our way towards the right book. Slowness incorporates time for reading the back cover, and taking note of the publisher and the publishing year. Slowness incorporates time for Craig to scan hundreds of book spines and hand me a slim poetry book. It was the first English translation of a long poem written in Spanish nearly fifty years ago. Translated by a Portland local, and published by a Brooklyn-based project with a long mission statement about adding new voices to the literary cannon on the back pages.

Moving slowly around a bookshop also makes room for rain showers to come and go, and to step out onto the street at the right moment when the sun is out and hot, drying off park benches so that one can start reading.

“I am going to the Disaster Zone/sailing my poem/ through the veins of the world”

“Voy a la Zona de Desastre/navegando en mi poema/por las venas del mundo”

There are some books to read in a refined manner while sipping your favorite espresso drink in a cafe. Hikuri (Peyote) has to be read somewhere more freeing, so that it can be spoken out-loud in order to ride the wave of its rhythm. Read out-loud in order to ride the wave of Jose Vicente Anaya’s journey from psychedelic blast-off to local utopia, and urban dystopia. To pan from love poem to definition to ego death and conversation amongst poets. All of these scenes occur in a hundred page poem. Or rather, a poemario, defined as: a collection of poems that follow a common thread. For this reason it is hard not to draw the comparison to Allen Ginsberg’s HOWL. HOWL -- a cry of sorrow, lamenting America’s sickness. Hikuri -- a howl of the soul, as it realizes how estranged it has been from its spiritual and indigenous home. It seems to be no mistake that Joshua Pollock translates ‘grita’ to ‘howl’ on the very first page, which more traditionally translates to ‘scream’ ‘shout’ or ‘yell’.

The poem took me along for the ride, on a trip, despite being warned that “Ships that explore space/don’t return;/they fly until infinity is lost...” “Las naves que exploran el espacio/no vuelven;/vuelan hasta perder el infinito...”

Hikuri (Peyote). The dark goddess who is a hundred spiders, or a woman both orb-like and triangular, or egrets dispersed through a field of manure. If you have not had a hero’s dose of a trip before, it may be harder to follow the journey of this poem. I would like to think that its power extends beyond, touching those who have never touched anything like it before... but I had already dove down parallel rabbit holes long before this book found its way into my hands. Being an adventurer, one who seeks out new words and phrases, lost histories and strange places-- I, too, have found myself “leaving on the next train to the unknown/and... again?” “me largo en el proximo tren desconocido/y... de nuevo?”

On one of such voyages, I had an intense urge to “join the conversation”. I felt that I was on the edge, that I could almost just peel back one more layer and be there, with every writer that had ever inspired me. Clearly, Jose Vicente Anaya successfully peeled back this last layer. This poemario is like a breadcrumb trail into the heart of Infrarealism, the movement that he was immersed in while staying around Mexico City. The movement that pulls from so many artistic influences around the world, and draws more radical conclusions.

Infrarealism, labeled as ‘a nonsense movement’ and ‘cultural terrorism’ by the Mexican government during its peak in the 1970s and 80s, rejected status success and poetic structure. Rejected the traditional ways that culture interacts with society. As it says in the Chicago Review’s 2017 feature on Infrarealism, “If the main principle of Infrarealism has been never to participate in or create groups of power, then the primary tactic has been not to publish—not through the official channels of the Mexican literary establishment, but also often not at all.” More often than publishing, these Infrarealists disrupted literary readings and releases as a form of protest against the fact that all successful writers in Mexico weave their way into fortune through government connections and social climbing. The Infrarealists created a separate social sphere, a free space where they could unify life and poetry.

Throughout Hikuri, Anaya sprinkles the names of many of his influences. Some are Infrarealists, and many are other poets that Anaya wishes to respond to. It is an enormous conversation between movements, cultures, decades, and philosophical minds. The Avant-Guard, German Romanticism, Surrealism, Modernist Poetry, Russian Futurism -- it was one of those trips where you can see the whole world from the outside, and the way that all of these intricate cultures and views and systems have interacted to form this -- and it is made clear to you that of course, after all of this scrambling, we are living in a disoriented time!

It is likely that many people living in the United States are not familiar with the people involved in the conversation that Anaya is facilitating. Perhaps that is due to the insane statistic that is cited at the end of this book: less than three percent of all books published in the United States are translations, and less than one percent are works of poetry or fiction. This poemario is published as a part of a project called GLOSSARIUM: UNSILENCED TEXTS, which is under a publishing house named THE OPERATING SYSTEM, based out of Brooklyn. In 2019 they estimated that they raised the amount of translated books of literature published in the U.S. by one percent, all on their lonesome. This project is the coolest because it lays out plainly the role that translation can play in diversifying minds.

“visionary poems

that surrender themselves to the wind

extant--- emerging--- they will exist

in what irrevocably ends”

“poemas iluminados

que se entregan al viento

viven--- vienen--- viviran

en lo que acaba sin retorno”

This is a poem that floated through the shifting winds of recent eras. Written first in the mind, then on leaves of paper in 1978, and finally printed in book-form in 1987. It only drifted over the border, in its English form, in 2020. Perhaps this is what Jose Vicente Anaya really wants to tell us. He tells us in the interview included at the end of this poemario that his poetry comes to him in visions, that it is channeled from another realm. In the above verse he puts words to the most tender of the countercultural poet’s longing, voices their hunch. That we write to be a part of the art of the END.

Curiously, it may have been a gift that so many Infrarealist works have never made it into English. For if they ever had gained literary recognition and merit in our capitalist epitome, it may have created a paradox so painful that it could destroy. When subversion is incorporated, when alternative becomes popular, becomes commodity, then what?

“what I write in the air

is worth more / that’s why I write here /”

“lo que escribo en el aire

vale mas / por eso escribo aqui”

Jose Vicente Anaya passed away in 2020. As Anaya wrote in Hikuri, and Joshua Pollock repeats in memorarium, I will echo once more: I stand with the dead in their lost causes.

Estoy con los seres muertos en las causas perdidas

Bookstore Creep contains recommendations from the continuous investigation of Rosalie L.H. Caggiano into modern-day authors who are writing about the counterculture and the underground in the USO (The United States Of...). The USO is a zone that may encompass the whole of what is known as North America, or might not quite make it to the Southernmost and Northernmost hinterlands of what is known as Mexico or Canada. Rosalie searches for modern writers that upend the impression that “nobody does anything even remotely interesting in real life anymore”. She talks straight to the book-tenders of the City of Portland, exploring bookshop by bookshop instead of wallowing in the depths of the 129+ million books on Earth without guidance. She is beginning the construction of an extensive stainless-steel 3D diagram that documents the intricate webs of writer’s connections and histories, which become more and more clear with each column. This diagram already takes up most of her backyard.

More on Infrarealism and Jose Vicente Anaya:

↝ Roberto Bolano’s Infrarealist Manifesto

↝ Mario Santiago Papasquiaro’s Infrarealist Manifesto

“ART IN THIS COUNTRY HAS NOT ADVANCED PAST A LITTLE TECHNICAL COURSE FOR EXERCISING MEDIOCRITY DECORATIVELY”

↝ Awesome 14 page article on the Infrarealist movement

↝ The many with whom Anaya conversed in Hikuri

Artaud

Vallejo

Ginsberg

Holderlin

Rimbaud

Pound

Mayakovsky